|

Kung Tuyo na ang Luha Mo,

Aking Bayan

ni Amado V. Hernandez

Lumuha ka, aking Bayan: buong lungkot mong iluha

ang kawawang kapalaran ng lupain mong kawawa:

ang bandilang sagisag mo�y lukob ng dayong bandila,

pati wikang minana mo�y busabos ng ibang wika;

ganito ring araw noon nang agawan ka ng laya,

labintatlo ng Agosto nang saklutin ang Maynila.

Lumuha ka, habang sila ay palalong nagdiriwang,

sa libingan ng maliit, ang malaki�y may libangan;

katulad mo ay si Huli, naaliping bayad-utang,

katulad mo ay si Sisa, binaliw ng kahirapan;

walang lakas na magtanggol, walang tapang na lumaban,

tumataghoy, kung paslangin; tumatangis, kung nakawan!

Iluha mo ang sambuntong kasawiang nagtalakop

na sa iyo�y pampahirap, sa banyaga�y pampalusog:

ang lahat mong kayamana�y kamal-kamal na naubos,

ang lahat mong kalayaa�y sabay-sabay na natapos;

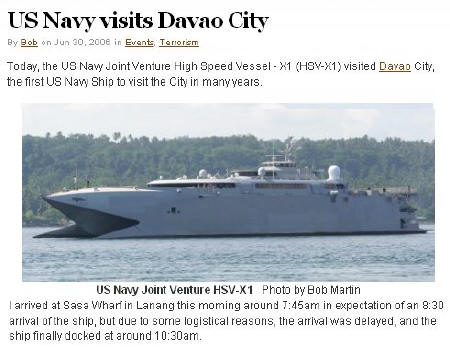

masdan mo ang iyong lupa, dayong hukbo�y nakatanod,

masdan mo ang iyong dagat, dayong bapor, nasa laot!

Lumuha ka kung sa puso ay nagmaliw na ang layon,

kung ang araw sa langit mo ay lagi nang dapithapon,

kung ang alon sa dagat mo ay ayaw nang magdaluyong,

kung ang bulkan sa dibdib mo ay hindi man umuungol,

kung wala nang maglalamay sa gabi ng pagbabangon,

lumuha ka nang lumuha�t ang laya mo�y nakaburol.

May araw ding ang luha mo�y masasaid, matutuyo,

may araw ding di na luha sa mata mong namumugto

ang dadaloy, kundi apoy, at apoy na kulay dugo,

samantalang and dugo mo ay aserong kumukulo;

sisigaw kang buong giting sa liyab ng libong sulo

at ang lumang tanikala�y lalagutin mo ng punglo! |

WHEN YOUR TEARS RUN DRY, MY

MOTHERLAND

Pilipino original by Amado V. Hernandez, �Kung Tuyo na ang Luha Mo,

Aking Bayan�

Free Verse Translation by Jose Maria Sison

Shed your tears, my motherland: let all your sorrow flow

Over the hapless fate of your hapless soil

The flag that is your symbol is shrouded by the alien flag

Even your inherited language is demeaned by another language;

Thus was the day when you were robbed of freedom

When Manila was seized on the thirteenth of August.

Shed your tears, while they gloatingly celebrate

On the graves of the downtrodden, the magnates are in revelry

You are like Huli, the enslaved debt peon

You are like Sisa, demented by suffering

Without strength to defend, without courage to fight

Wailing while being slaughtered, lamenting while being robbed.

Shed your tears over the heaps of misfortune

That inflict pain on you, that fatten the aliens

All your riches are wantonly squandered

All your freedoms quashed in one fell swoop

Behold your land, an alien army is guarding

Behold your seas, an alien ship is hovering.

Shed your tears if in your heart the purpose has waned

If the sun in your sky is always in twilight

If the waves of the sea have ceased to surge

If the volcanoes in your breast do not rage

If no one stands vigil on the eve of the uprising

Shed, oh shed your tears if your freedom lies in state.

The day will come when your tears run dry

The day will come when tears no longer flow from your swollen eyes

But fire, fire the color of blood

While your blood will be boiling steel

You shall shout with full courage in the flames of a thousand torches

And the old chains you shall destroy with gunfire.###

|

|

Amado V. Hernandez:

People�s Writer

Because of the sharp and

stirring literary expression of the social causes he pursued, Amado V.

Hernandez is rightly considered a prime example of the writer as agent of

social change and purveyor of people�s culture.

By Alexander Martin Remollino

Bulatlat.com

I distinctly remember that in one of our college classes in literature,

our professor asked the following question: �Should literature be for its

own sake, or should it espouse social causes?� As our professor herself

would later on explain, the question was a way of asking whether the

writer should be concerned with form or with content.

We can be sure that if the late writer Amado V. Hernandez, whose

centennial birth anniversary will be celebrated on Sept. 13, were asked

that question, he would have answered�without a moment�s hesitation,

without batting an eyelash�that writers have a responsibility to involve

themselves in society. As he said in his speech when he accepted the 1964

Manila Cultural Award (which is just one of the many awards he received),

�The days are gone when the artist was like Narcissus, adoring his own

image. Today the artist is witness to and part of the immediate present.�

As his very writings prove, in the manner that one of his literary idols,

Jose Rizal, proved decades before him; and another writer, Eman Lacaba,

would start to prove while he was still alive�espousing social causes does

not have to diminish the aesthetic quality of one�s literary output.

Society as truth

In his essay �The Filipino and the Man,� which he wrote as a college

freshman at the Ateneo de Manila University, Eman Lacaba said: �The

responsibility of any writer in the world is to write truthfully and

comprehensibly about the world he lives in, the world he remembers and

continues to know, the world he experiences.�

Hernandez, who was born decades before Lacaba, also knew this. And his

prolific and diverse writings attest to his vast knowledge of the reality

of human experience.

Hernandez�s grasp of the scope of human reality was so deep that he was

well aware that society and social phenomena, like romantic affairs which

comprise the greater bulk of subjects in the world�s body of literature,

are also parts of human reality. In fact to Hernandez, society and social

phenomena play the most prominent parts in the human drama: he knew

perfectly well that all human beings are inevitably affected by society

since they are all part of it.

Thus, even as he would sometimes write of a woman wooed with orchids, of a

lover�s Rip van Winkle heart, he wrote infinitely more of the battle

between the oppressor and the oppressed�and because he knew that rectitude

can never side with the oppressor, he in his writings showed unequivocal

support for the oppressed and undeniable hatred for the oppressor.

Hernandez wrote clearly and eloquently of enslavement in the hands of a

colonial power, of workers in unspeakable penury amidst unimaginable

abundance, of peasants stripped of their lands, of children begging on the

streets, of people eaten by the prisons for refusing to bow before

iniquity, of the heroism of fighters for freedom and justice. His poems,

articles, novels, short stories, and one-act plays contained such lucid

expositions of the social issues of the times in which he lived (issues

that are still very much with us), and were so splendidly written, that he

became (and still is) an icon for many a succeeding generation of

cause-oriented writers.

Among the people

One of Hernandez�s distinguishing marks is the fact that unlike so many

politicians who in their campaign speeches tell sob stories of how as boys

they had to catch frogs for supper because there was nothing else to eat,

he stayed by the side of the people of whom he was born�and served them to

his very last breath.

Hernandez was born on Sept. 13, 1903 but it is not quite clear where; the

conventional wisdom is that he was born in the slums of Tondo, where he

grew up, but a short story by Jun Cruz Reyes implies that his origins can

be traced to a town in Bulacan.

He took his pre-college education in public schools in Manila. After high

school he began the study of Fine Arts at the University of Santo Tomas,

where fellow cause-oriented writers Bien Lumbera and Rogelio Sicat also

studied. However, he did not finish his course, and instead settled for a

course under the American Correspondence Schools.

Afterwards he entered the worlds of journalism and literature. He would

climb the ladder and eventually become editor of Mabuhay in 1934, a post

he held until 1941. Even at the earliest days of his career he was already

writing against U.S. imperialism and social injustice.

When the Second World War broke out, he refused offers to collaborate with

the Japanese. He took to the hills and became an intelligence officer of a

guerilla unit.

In 1945, he co-founded the Philippine Newspaper Guild and the Congress of

Labor Organizations (CLO). He would become chairman of the CLO. These

organizations were in the forefront of struggles not only for press

freedom and better economic conditions for workers, but also against U.S.

economic domination and military intervention.

|

|

|

Hernandez was arrested in 1951

amidst a crackdown by the Quirino administration on both legal progressive

organizations and the underground Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas-Hukbong

Mapagpalaya ng Bayan. For five months he was held in solitary confinement,

after which he was charged with �rebellion complexed with murder and other

crimes.� He was convicted by the lower court and sentenced to imprisonment

for five years and six months. In 1956 he won temporary liberty, and after

eight more years was acquitted, with the Supreme Court ruling that there

is no such crime as rebellion complexed with murder.

After that, he became editor of the progressive newspapers

Makabayan and Ang Masa, and continued to

write poetry, fiction, and short drama. He also

resumed active participation in the people�s movement.

Aside from his work as writer and activist, he had a brief stint in

teaching, and also served four terms as a Manila councilor.

He died of heart attack in March 1970.

The writer as

hero

Amado V. Hernandez definitely has a place in the country�s pantheon of

heroes, along with Emilio Jacinto, Apolinario Mabini, and Aurelio

Tolentino�like whom he was a brilliant writer with unswerving dedication

to the fight for freedom and justice. Like Mabini and

Tolentino, he suffered for his refusal to accept a status quo

characterized by a rule of a small elite and their foreign masters, but

held fast to his convictions to his last breath.

Because of the sharp and stirring literary expression of the social causes

he pursued, he is rightly considered a prime example of the writer as

agent of social change and purveyor of people�s culture.

He may not be as well-known as he deserves to be, as activist artist

Nanding Josef lamented in a recent press conference, but that does not

mean he is unworthy of admiration. In fact he is infinitely worthier of

admiration than the celebrities whose antics today�s pop culture is

heavily drawn from. Bulatlat.com

|

![]()