By Oliver X.A. Reyes and Erwin Romulo | Jul 13, 2017

ESQUIRE: During what precise period were you directly involved in the leadership of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP)-New People’s Army (NPA)? What was your role in the organization after your release from imprisonment in 1986 and for how long did that role last? What is your current position, if any, with the CPP-NPA?

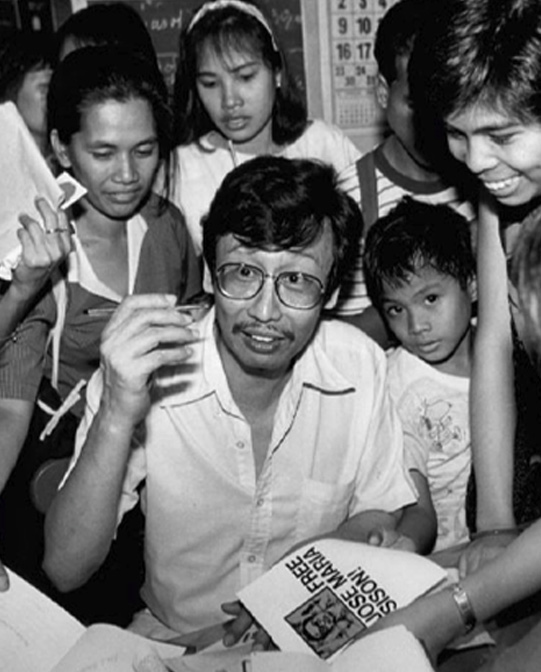

JOSE MARIA SISON: I was the Chairman of the Central Committee of the CPP and was the over-all political officer of the NPA from the respective founding dates of the two organizations to the date of my capture by the Marcos fascist dictatorship on November 10, 1977. Since my release from military detention in 1986, I have been an academic and writer and called the Founding Chairman of the CPP by many journalists, without any objection from me because of the historicity of the title. Sometimes, I have been called the spiritual icon of the revolutionary movement. But more humbly speaking, I have been the Chief Political Consultant of the National Democratic Front Philippines (NDFP) in peace negotiations since 1992.

The Dutch courts and the European Court of Justice ruled in 2007 and 2009 respectively that I do not operate or run the CPP and NPA. In April 2013, the Government of the Philippines (GPH) through its presidential adviser on the peace process and negotiating panel chairman proclaimed that I have no influence over the CPP, NPA, and NDFP and thus decided to terminate the peace negotiations with the NDFP Negotiating Panel that is based in The Netherlands.

ESQ: What must the government do in order to resume the peace talks? What new steps would the NDFP be willing to take to enable the peace talks to resume?

JMS: The resumption of peace talks is possible. The position of the NDFP is that in principle the peace negotiations are still going on in the absence of a formal notice of termination from the GPH. The GPH can simply contact the NDFP directly or through the Royal Norwegian Government to express its desire to resume formal talks. Formal talks are done by the Negotiating Panels of the GPH and the NDFP. The NDFP does not set preconditions for such talks even as it demands compliance with existing agreements. The NDFP does not have to do anything but to wait for the approach of the GPH. It was the GPH last April which announced to the press that it was terminating the peace negotiations. At the same time, it has not given the formal notice of termination either because it arrogantly rejects all the previous agreements or it gives space for resumption of talks.

ESQ: In Latin America, many unapologetically leftist candidates have made successful presidential runs, such as Chavez of Venezuela, Morales of Bolivia, Correa of Ecuador, and even Lula of Brazil. Do you think it is possible for a candidate with a similar ideology to succeed under the prevailing electoral framework in the Philippines? Why do you think those candidates in Latin America were able to gain power through the ballot?

JMS: It is possible to have anti-imperialist and progressive presidents in the Philippines like the late Chavez, Morales and others if the GPH-NDFP peace negotiations succeed in making comprehensive agreements on social, economic, and political reforms to establish a just peace. But at the moment, the unreformed political and electoral system prevents anti-imperialist and progressive presidential candidates. Revolutionary observers say that Chavez, Morales, Correa and Lula have been successful in elections within the ruling system of the big bourgeoisie and the landlords because they are not Left enough to frighten the U.S. and the local reactionary classes although they are Left enough to get the votes of the workers and peasants by asserting a certain measure of national independence and some social reforms. At any rate, the NDFP has been trying hard to create conditions similar to those in Venezuela and other countries in which patriots and progressives are not killed by the reactionaries but are elected by advocating national independence, democracy, social justice, development through land reform and national industrialization and a patriotic and progressive culture.

ESQ: Do you think that an anti-imperialist and progressive candidate could be democratically elected as President within the next 20 years?

JMS: Yes, within 20 years, there is more than enough time for the crises of the ruling system and global system, the relentless struggle of the people for national liberation and democracy and the peace negotiations to generate conditions for the election of a President who is anti-imperialist and progressive, as in the countries of Latin America that you have mentioned.

ESQ: You were noted for steering the Philippine communist movement away from Soviet ideology in favor of Maoist thought. How would you characterize the current Chinese leadership’s adherence to communist ideology or the ideals of Mao?

JMS: The post-Mao leadership in the Chinese Communist Party is the product of the Dengist counterrevolution and the fundamental shift from the socialist road to the capitalist road. By certain measures, China has become a major capitalist power. The post-Mao leadership in China does not really adhere to the revolutionary teachings of Mao and the previous great communist thinkers and leaders. But the prestige of Mao and the Communist Party in revolutionary times is being used by the current capitalist leaders of China to legitimize their rule.

ESQ: You wrote Philippine Society and Revolution under the name Amado Guerrero. Are there any of its organizing premises which you think are no longer applicable today?

JMS: The basic description of Philippine society as semi-colonial and semi-feudal, the need for a people’s democratic revolution, the workers, peasants, and urban petty bourgeoisie as the motive forces of the revolution, the big compradors and landlords as the main adversaries and the socialist perspective of the revolution remain valid. I do not engage in nitpicking on my own work. The basic propositions remain valid. The U.S. and local exploiting classes would not be so much bothered about the people’s democratic revolution if this has lost its validity. The bankruptcy of the neoliberal economic policy has brought about a crisis that is comparable to the Great Depression and is generating social turmoil, wars of aggression and revolutionary wars on a global scale.

ESQ: Philippine Society and Revolution strongly articulates the imbalance of Philippine-U.S. relations, as they had existed since 1898. However, with the withdrawal of the U.S. bases and the lapse of highly imbalanced laws such as the Parity Act, the degree of intervention of the United States in Philippine affairs has seemingly decreased. Would you dispute that assessment?

JMS: Serious contradictions, not just imbalances, have characterized the relations of the US with the Philippines and the Filipino people. The US remains in control of Philippine economics, politics, military and culture at the expense of the broad masses of the people. Even without the flagrant US military bases, the US has controlled the puppet regime and the Philippine armed forces and police through advice, training, military supplies, and other means of control. Since the so-called war on terror by the US and more so since the so-called U.S. pivot or strategic shift to East Asia, the U.S. has been desirous of having more than forward stations inside Philippine military facilities. It is aiming to establish U.S. military bases. At any rate, U.S. air and naval vessels are patrolling the Philippines and the seas around more frequently under various pretexts. Since the economic reconstruction of Japan and Europe in the 1960s, the U.S. has taken cover under multilateral economic and trade agreements, aside from bilateral ones, to continue dominating the Philippine economy and in effect even Philippine politics and culture. The U.S. controls the Philippines though bilateral arrangements and through such multilateral agencies as IMF, World Bank, and WTO.

ESQ: The Canadian academic Dominique Caouette has been quoted as saying about the CPP-NPA-led armed struggle: “There was never one Philippine Revolution but several revolutions ongoing at the same time.” Do you agree with this assessment?

JMS: The Philippine revolution is being waged simultaneously in various ways: politically, economically, socially and culturally. However, these ways are interrelated and coordinated even if distinguishable from one another. You can ask Caouette whether he agrees with me. The people’s war answers the central question of revolution, which is to seize power. Even before nationwide seizure of power, local organs of the people’s democratic government are already being established to displace the reactionary government. Socio-economic revolution is going on through genuine land reform, promoting cooperative production and favoring Filipino-owned industries. The cultural revolution is going on. It is advancing the cause of a national, scientific and people-serving cultural and educational system. Revolutionary educators, writers and artists, scientists, and technologists and other cultural workers and the great mass of activists of the national democratic movement are waging a cultural revolution.

ESQ: What concrete products of this cultural revolution have had a marked impact on Philippine public life over the last few decades?

JMS: Since the 1960s, the cultural revolution along the national democratic line has continued inside and outside the schools and other institutions. It has popularized mass actions (the parliament of the street) to call for substantive change. It created the First Quarter Storm of 1970 which presaged the Edsa uprising that overthrew the Marcos dictatorship. It has brought forward a new democratic type of thinking and mass activity in the progressive party list groups, in the trade unions and other mass organizations, in the professions and, of course, in the armed revolution. It has promoted the national language and literature as well as the regional languages and literature. It has generated thinkers, writers, artists, scientists, and technologists who are committed to serve the people.

ESQ: One of the defining characteristics of the Maoist revolutionary model was the adoption of armed guerrilla tactics. It is an approach that inevitably leads to deaths among guerrilla fighters, the military, and civilians caught in the cross-fire. When you think about the thousands of fighters and civilians who had lost their lives since the 1960s, what thoughts cross your mind?

JMS: My thoughts go to the Bible, which says that just war can be waged against injustice, oppression and tyranny. The daily violence of exploitation goes on even when the exploited people are not resisting. When people wage people’s war or guerrilla warfare, they have hope and have a chance of winning. The Filipino people celebrate the revolutionary wars against Spanish colonialism, U.S. imperialism and Japanese fascism. Violence from the oppressed and exploited comes after the fact of violence from the imperialists, the big compradors, the landlords and corrupt government officials to accumulate wealth and cause poverty and hunger and deprive the people of timely and sufficient medical care. Those who accumulate wealth and power control the Philippine state. With the support of the US, they use organized violence (military, police, the courts and prisons) to preserve and protect their privileges against the people. It is said that tens of thousands have been killed in the current civil war in the Philippines since 1969. More than 90 per cent of them have been killed by the military, police and paramilitary forces of the reactionary state. They tend to kill many because most of the time they do not know who are the revolutionaries. Most of the victims are individuals and people who are merely suspected of being revolutionaries or of aiding the revolutionaries. It is not true that people are being killed merely in the crossfire. They are killed by the reactionary armed forces cold-bloodedly or in blind rage.

ESQ: Were you involved in any incidents wherein you had to take part as an armed combatant? How did those experiences (or those experiences of comrades) bear impact on the preferred strategies then of armed combat?

JMS: Whenever I expressed the wish to join a combat operation, the most responsible Party comrades and Red commanders dissuaded me from joining because supposedly my role was not in combat. But I was in the midst of firefights a number of times because our camp was being attacked by the enemy. During camping and marches, I simply had to share weal and woe and the risks with the Red fighters. I took active part in politico-military training for the Red commanders and fighters of the New People’s Army and in planning and reviewing tactical offensives. We learned from each other how to carry out tactical offensives in line with the strategy of people’s war. I joined the military exercises, including the analysis and simulation of a major tactical offensive. My favorite part in military exercises was to demonstrate how to shoot accurately with the rifle. I was a marksman in ROTC.

ESQ: Have you had the opportunity to encounter or communicate with a family member of a soldier who had died because of the armed conflict? If you had, what was that encounter like?

JMS: I have been approached by close relatives of those held as political prisoners of war by the New People’s Army and I have helped them to the best of my ability. But I have not been approached by any family member of a soldier killed in the civil war. But if I were approached, I would express sympathy at a personal and humanitarian level. If the soldier came from the working class and peasantry, I could be tempted to say that he should have fought on the revolutionary side. But I would not yield to the temptation of moralizing or lecturing because it would run counter to the expression of sympathy and would be overstating the obvious that the exploited sometimes join the reactionary army because they have no other job opportunity.

ESQ: For many, the defining statistic of the armed struggle has been the number of lives lost. How would you convince them that despite that statistic, there was a point to the armed struggle, or that there is a purpose for it to continue?

JMS: I think that it is the system of oppression and exploitation that engenders the revolutionary armed struggle of the oppressed and exploited. The people fight back the more they are subjected to oppression and exploitation. Thus, the armed strength of the NPA has grown from the level of 6,100 high-powered rifles to nearly 10,000 contrary to the false claims of the Arroyo and Aquino regimes that the NPA has been reduced to only 4000 from a level of 25,000 in 1986. More people are joining the armed revolution because they abhor the daily violence of exploitation and the gross and systematic violations of human rights. These are being committed with impunity by those in power. Like our revolutionary forefathers, our revolutionary contemporaries fight even harder because of the killing rampages of their enemy with superior military power.

ESQ: You are on record as saying that there have been hundreds of false charges made against you, many in connection with alleged killings of members of the NPA through purges made in the 1980s. Do you believe that these charges were made in connection with perceived split within the revolutionary movement by leaders that you have criticized such as Romy Kintanar and Popoy Lagman?

JMS: I was under maximum military detention from November 10, 1977 to March 5, 1986. From the time I was released, I became preoccupied with public speeches, academic lectures and press interviews until I left the Philippines on August 31, 1986. No chance for me to be involved in any of the wrongful killings, which were ascribed to Romy Kintanar and Popoy Lagman among others. But certain anti-communist quarters inside and outside of the reactionary armed forces deliberately try to confuse people by mixing up Kampanyang Ahos and other bloody witch-hunts of the 1980s with the Second Great Rectification Movement, which condemned and repudiated these crimes. The rectification movement was a campaign of ideological and political education within the CPP from 1992 to 1998 in order to correct major ideological and political errors which resulted in certain setbacks and even crimes.

ESQ: How would you define the degree of care that armed units of the CPP-NPA have taken in the protection of human rights, especially of civilians caught in conflict or of soldiers who have been captured? What actions should the current NPA take in response to the recent shooting of the wife of Vice-President Guingona by alleged members of the NPA?

JMS: The Red commanders and fighters of the NPA are sworn to uphold, defend and promote the human rights of the people. They are bound by the principles and policies of the CPP, NPA and NDFP in this regard. These include the Three Rules of Discipline and Eight Points of Attention, the Geneva Conventions and its Protocols and the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law. The Red commanders and fighters cannot preserve their strength and win battles against the military superiority of the reactionary armed forces if they do not protect the national and democratic rights of the people. They have political superiority over the reactionary army because they are the best sons and daughters of the people, they fight for the workers and peasants and have the inexhaustible support of the people. The CPP, NPA and NDFP have already declared that there was a misencounter between an NPA checkpoint force and the security force of Mrs. Guingona as mayor, because the latter had refused to stop and had run over the NPA checkpoint. They have expressed regrets and have apologized to the Guingona family. Nevertheless, the NDFP Negotiating Panel has learned that further investigations are being made in order to test the previous findings and conclusions.

ESQ: The matter of “revolutionary taxes” exacted by the NPA on political candidates or business enterprises in the countryside has been often reported in Philippine media. What had been the justification for such a practice, and should that practice continue to this day?

JMS: The people’s democratic government has repeatedly made clear that it does not impose any tax on any candidate in the reactionary elections. The CPP has denied the claims of the reactionary government and other anticommunist entities that tax is imposed on electoral candidates. As a matter of united front policy, the revolutionary movement tolerates the electoral struggle of patriotic and progressive groups and elements. The people’s democratic government taxes permissible businesses. Taxation is a function of the people’s government. The tax revenues are used to finance the costs of administration, defense, land reform work, production assistance education, health work, cultural activities and other social services provided by the people’s democratic government and the mass organizations.

ESQ: How do you feel today about the so-called Declaration of Autonomy of the Manila-Rizal Regional Committee of the CPP? Is there a possibility of reconciliation or unification with the other perceived ideological-left movement represented by Akbayan? What accommodations in ideology should materialize in order that such reconciliation could happen?

JMS: The Second Great Rectification Movement and the consequent intensified mass work by the revolutionary forces in both urban and rural areas overcame all the wrecking operations done by elements who separated from the CPP and later exposed themselves fully as special agents of the reactionary government. The Popoy Lagman group became an even smaller and inconsequential group serving as organizers of yellow unions and bourgeois politicians. Those previously misled by that group have returned to the CPP as early as 1994 according to reliable reports. There is no basis for reconciliation or unification of the CPP with Akbayan for the simple reason that Akbayan has always made clear that it is not communist and that it is not revolutionary but reformist. I have not seen any CPP statement condemning any dropout from the CPP for joining Akbayan.

ESQ: Do you believe that the changes to Philippine society that the armed struggle fought for can occur under the framework of the current Philippine Constitution?

JMS: The NDFP is seeking political and constitutional reforms through the peace negotiations because the constitution of the reactionary government, as it is now, will not allow basic social and economic reforms. The current constitution favors the property rights and interests of the big compradors and landlords as well as the US and other multinational firms against the toiling masses of workers and peasants and even against the middle class.

ESQ: Would the revision or the adoption of a new Constitution be among your negotiating points should peace talks resume with the government?

JMS: The third item in the substantive agenda of the peace negotiations is political and constitutional reforms. The Comprehensive Agreement on Political and Constitutional Reforms shall stipulate the constitutional reforms. We can anticipate proposals to simply amend the existing GPH constitution or to use the constitutions of the GPH and the people’s revolutionary government as the basis for making a new constitution.

ESQ: Bayan Muna has been an active participant in Congress since the introduction of the party-list system. How do you assess the effectivity of Bayan Muna and similarly oriented parties in the Philippine legislature? Has the legislative role of Bayan Muna have had an impact on the role and tactics of the NPA?

JMS: The representatives of Bayan Muna and other progressive party list groups, which advocate national independence and democracy, have done well in proposing patriotic and progressive bills for the benefit of the people. Some of the bills pass with a tolerable amount of amendments and other bills are not passed or are mutilated by amendments. What the progressive party list groups can do in the reactionary Congress is extremely limited. It does not have much impact on the role and tactics of the NPA by way of changing them. Definitely, it does not persuade the NPA commanders and fighters to cease fighting and join the parliamentary struggle.

ESQ: What unexpected lessons did you learn during the decade or so you lived “underground” in the Philippines?

JMS: In the 1970s, I was sure and firm about the general line of people’s democratic revolution through protracted people’s war. But there were unexpected lessons to learn from the variables of the situation and from the surprises that the enemy tried to pull. Forced disappearances, arrests, torture and massacres by the enemy occurred frequently and suddenly and I had to think how to avoid or counteract these and how the revolutionary forces could move forward.

ESQ: What insights, if any, have you taken from Dutch or European politics or culture that you feel would find application in the Philippines?

JMS: We can learn from the history of Europe and The Netherlands that there must be a political will to break up the feudal system and carry out the industrial development of the Philippines. The liberal democratic revolution of the bourgeoisie and the revolutionary strivings of the industrial proletariat for socialism have contributed to economic, social, political and cultural development. If we can carry out genuine land reform and national industrialization, then we can create the broad base for political and cultural development. We can build a New Philippines that is independent, democratic, socially just, progressive and peaceful. Unlike the capitalist powers of Europe, we can strive to make all-round advances without engaging in colonialism and imperialism and without having a big bourgeoisie that has brought about the current crisis that is comparable to the Great Depression.

ESQ: Have you kept up with contemporary Filipino culture? What was the last Filipino movie that you had seen?

JMS: Of course, I have kept up with contemporary Filipino culture, including literature, music, dance, painting, sculpture, films and so on. I saw most recently the film Migrante.

ESQ: Have you thought about that first day upon your return to the Philippines? What do you see yourself doing on that first day?

JMS: I will have a big party with relatives and friends to exchange pleasantries and start renewing personal relations.

This article was originally published in the July 2013 issue of Esquire Philippines. Edits have been made by the Esquiremag.ph editors.