Neocolonialism

Operation Pacific Eagle: Duterte Falls in Line with US Plans for the Philippines

Whatever anti-imperialist intentions the notoriously zig-zag Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte may have begun with, his natural affinity for the like-souled Trump has quickly brought him around to the traditional symbiosis with the U.S. and its use of his country for a regional launchpad.

by Elliott Gabriel

February 15th, 2018

By Elliott Gabriel

In the second part of this MPN exclusive, we examine the U.S. military’s latest intervention in Asia, its 120 years of imperialist domination in the Philippines, and Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s half-hearted push for independence from Washington. We speak to exiled Filipino revolutionary Jose Maria Sison and Professors William I. Robinson and Roland Simbulan.

In Part Three, we will conclude with a comparison of Operation Pacific Eagle to the notorious counterinsurgency initiative “Plan Colombia,” and look at how the new Pentagon mission enables the U.S. to continue encircling China with its military bases.

In Part One, we spoke to Ka Oris of the New People’s Army and the professors about the armed struggle on the southern island of Mindanao and its nearly trillion dollars in mineral deposits — a crucial motive for Washington to prioritize the Philippines as a major military theater on the same scale as Syria and Iraq.

MANILA, PHILIPPINES — By all appearances, Operation Pacific Eagle — the U.S. military’s new overseas contingency operation to team up with the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) to fight so-called “extremist” groups — is a mission conceived to never end.

Packaged as an extension of the fight against the Islamic State (ISIS) group’s Southeast Asian cohorts, Operation Pacific Eagle has been confirmed by a U.S. government report as entailing that U.S. special operations personnel accompany AFP troops in all of its military operations, especially on the large southern island of Mindanao. A virtually limitless sum of money will also be allowed to fund the mission, which will be prioritized on the same level as Operation Enduring Freedom in Iraq and Syria.

As MintPress detailed in Part I of this series, the alleged presence of so-called “ISIS-P” (Islamic State group in the Philippines) militants in Mindanao, which remains under martial law, provides a convenient excuse for the entrenching of U.S. Armed Forces to assist the AFP in halting “radicalization and violent extremism” in the country.

Launched last September but only announced last month, the mission ensures that the U.S. will play a direct role in armed operations aimed at quelling the nearly half-century-old insurgency of the Communist Party of the Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP-NPA), who were tagged as “terrorists” by President Rodrigo Duterte after peace talks between Manila and the leftists dramatically fell apart last year.

The multi-faceted armed struggles and mass movements of the country’s poor majority have been the main engine of the Filipino peoples’ long push for national self-determination, genuine independence and a democratically-run economy — a fight that dates back to the era of Spanish theocratic rule. It was precisely the demand for an end to the U.S. stranglehold on the Philippines that paved the way for Duterte, who promised to forge an independent foreign policy, to be elected in 2016 in a tactical alliance with the anti-imperialist left.

University of the Philippines Professor Roland Simbulan, an author of numerous books and articles on U.S. military activities in the Philippines and East Asia, sees Operation Pacific Eagle as a mission meant to assist Duterte as he stifles his domestic opposition, in exchange for indefinitely securing the country — described by Trump as a “prime piece of real estate” — as a U.S. base for potential military actions against China.

“The Philippines is the United States’ aircraft carrier in the Western Pacific, directed at any rising imperial power that challenges [the U.S.] economically and militarily,” Simbulan told MintPress News, continuing:

“The U.S. is using every opportunity to back Duterte’s combined anti-terror and anti-drug campaign to build its strategic military platforms in the Western Pacific. This operation has the goal of regaining leverage and reimposing U.S. domination to launch direct military interventions. This can only happen if it is able to recalibrate its military presence – through Pacific Eagle – in the Philippines and the Western Pacific.”

These comments may come as a surprise for readers who associate Duterte with his previous vows to realign the country with Russia and China. The erratic head of state, however, has shown himself capable of both admitting to (and retracting said admission of) his own abuse of the deadly opioid Fentanyl while pursuing his deadly war on drugs, and has even likened himself to Hitler before later kissing up to apartheid Israel.

Duterte’s erratic “anti-imperialism”

Shortly after assuming office on June 30, 2016, Duterte began striking out at Manila’s traditional allies in Washington, especially after launching a vigilante-style war on drugs that, according to some estimates, has claimed the lives of well over 13,000 alleged drug users and peddlers.

Criticism from then-President Barack Obama provoked an especially fierce reaction from the volatile Philippine head of state, who told the U.S. leader to “go to hell,” while threatening to dramatically scale back the U.S. military’s presence in the country.

“These white people, those from [the European Union], the ignorant Americans, pretending to be, this Obama,” Duterte commented at the time. “You are so black and arrogant. [He] reprimanded me. Why [do] you reprimand me? I’m the president of a country.”

Shortly afterward, Duterte visited Beijing’s Great Hall of the People to declare his “separation from the United States,” telling a bemused audience of Chinese businessmen and officials that “Americans are loud, sometimes rowdy,” and unaccustomed to speaking in a manner “adjusted to civility.” He went on:

“Both in military, not maybe social, but economics also. America has lost … I’ve realigned myself in your ideological flow and maybe I will also go to Russia to talk to [President Vladimir] Putin and tell him that there are three of us against the world – China, Philippines and Russia. It’s the only way.”

Among those urging an independent foreign policy course free of U.S. diktat, Duterte’s comments were greeted with cautious optimism. This was, after all, a former mayor of Davao City who had denounced U.S. covert operations in Mindanao and rebuffed the Americans’ demands to use the city’s airport as a base for military drones.

Throughout nearly two years in office, however, Duterte has failed to review or cancel any of Manila’s lopsided treaties or agreements with the U.S., such as the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA).

“The occasional anti-U.S. rhetoric is mainly a defensive reaction to anti-EJK [extrajudicial killing] elements in the U.S., EU and UN who have articulated concerns about the deteriorating human-rights situation in the country,” Simbulan noted.

Duterte’s past angry words bear little meaning, according to exiled Communist Party of the Philippines founding chairman Jose Maria Sison, a former college instructor to the president. Last May, Sison noted that his former pupil has long been known for “talking or acting in the style of the left, center and right, whichever serves him best from moment to moment.” Less charitably, last month Sison described Duterte as a “nutty shithole” like “his imperialist master,” Donald Trump.

Sison told MintPress:

“We should not be confused by the previous tantrums of Duterte against Obama, some U.S. Congress leaders, and the U.S.-based human rights [groups] who wished to pressure Duterte in the name of human rights to refrain from, or go slow on, the mass murder of the suspected drug users and pushers or else suffer reductions in U.S. military assistance.

To make his tantrums more impressive, Duterte prated about an independent foreign policy, either by playing down the U.S. and playing up China and Russia, or simply by playing off one foreign power against another to his advantage.”

In the meantime, the country’s military establishment – a traditional bastion of pro-U.S. sentiment – chafed at Duterte’s foreign policy swerves, yet ultimately endured them, especially once it became clear that his spat with Obama was merely personal. By last September, the Philippine president was even joking that Department of National Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana, who was stationed in Washington as an attaché from 2002 to 2016, was a secret CIA agent — a strange joke considering that the DND chief was, indeed, seen by critics as representing U.S. interests in the Manila government.

“All the while [as Duterte made his anti-U.S. comments] … Lorenzana was assuring the CIA and Pentagon that Duterte was under control and was ready to play ball with his friend and psycho-political lookalike, Trump,” Sison added.

The clear rebound in U.S.-Philippine relations was confirmed last November, when Duterte sang a Filipino love song to Trump, “upon the orders of the commander-in-chief of the United States” (as he put it), that included evocative lyrics that translate as: “You are the light in my world, a half of this heart of mine.”

For 120 years, the U.S. has unceasingly sought to dominate the multi-ethnic and strategically located Philippine nation. This crucial history is key to understanding why the chief executive of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines has been unable – if not unwilling – to break from Washington’s stifling embrace.

What’s past is prologue: U.S. genocide in the Philippines

While seldom recognized in U.S. history books, the predatory war on the Philippines was a watershed moment in the creation of the United States’ overseas empire.

When an exhausted and defeated Spanish Empire sold the Philippines to the United States in 1898 for $20 million, the country was still in the throes of the Philippine Revolution. By taking ownership of the country, invading U.S. forces also took ownership of the counter-insurgency campaign that the Spanish colonizers had failed to successfully carry through.

Possessed by the pseudo-religious ideology of “Manifest Destiny” — and unable to find a frontier at home to conquer after aggressively seizing over half of Mexico, purchasing Alaska and overthrowing the native Kingdom of Hawaii — the U.S. found in the Philippine nationalists the perfect target for a new genocidal campaign similar to the one carried out versus the so-called “savage redskin” indigenous nations that originally populated North America.

For two decades, the U.S. military waged a war of extermination. Guerilla insurgents, branded “brigands” and “thieves” by President Theodore Roosevelt, faced torture techniques such as waterboarding, savage beatings, and summary execution by troops under the command of storied U.S. military heroes like Generals John J. Pershing and Arthur MacArthur Jr., the father of Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

Celebrated British poet and author Rudyard Kipling hailed the U.S. intervention in his famous poem “The White Man’s Burden,” which was greeted by The New York Times as the “strongest argument yet published in favor of expansion.” The poem — an impassioned paean to colonialism and the quest to conquer “half-devil and half-child” peoples such as the combative Filipinos — played strongly on the self-aggrandizing ethnocentrism that gripped U.S. leaders.

In a 2003 article that analyzed the poem’s influence while comparing the U.S. colonization of the Philippines to the still-young U.S. occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq, sociologist and editor of The Monthly Review John Bellamy Foster noted:

Today’s imperialists see Kipling’s poem mainly as an attempt to stiffen the spine of the U.S. ruling class of his day in preparation for what he called ‘the savage wars of peace.’ And it is precisely in this way that they now allude to the ‘white man’s burden’ in relation to the twenty-first century. Thus for the Economist magazine the question is simply whether the United States is ‘prepared to shoulder the white man’s burden across the Middle East.’”

Nearly 1.5 million out of six million Filipinos – primarily the Moro Muslims in the southern island of Mindanao – were wiped out in the bloody onslaught that followed, with counter-insurgency tactics that foreshadowed atrocities like the My Lai Massacre during the Vietnam War.

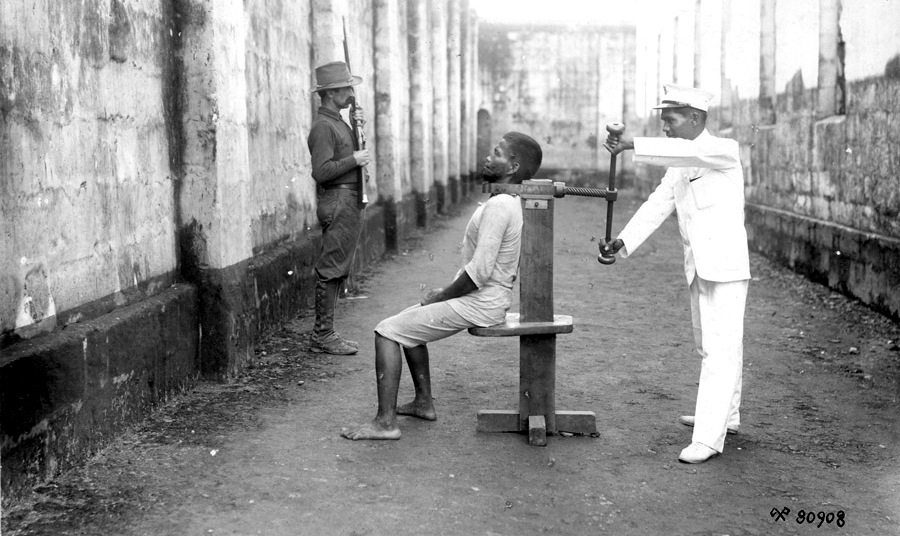

An American soldier stands guard in the background. (Photo: National Archives of the Philippines)

Writing to the Fairfield Journal of Maine in 1899, U.S. Marine sergeant Howard McFarland explained his troops’ methods in the language of white-supremacist terrorism:

There were 1008 dead nggers, and a great many wounded. We burned all their houses. I don’t know how many men, women and children the Tennessee boys did kill. They wouldn’t take any prisoners … At the best, this is a very rich country; and we want it. My way of getting it would be to put a regiment into a skirmish line, and blow every ngger into a ngger heaven. On Thursday, March 29, eighteen of my company killed seventy-five ngger bolo men and ten of the n*gger gunners. When we find one that is not dead, we have bayonets.

Wryly commenting on the naked imperialism of the world’s great powers who united in “peace” for “mutual murder and the torch” in colonized lands, Polish-born German revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg wrote:

On the Asiatic coast, washed by the waves of the ocean, lie the smiling Philippines […] [W]e saw the benevolent Yankees, we saw the Washington Senate at work there. Not fire-spewing mountains – there, American rifles mowed down human lives in heaps.”

After pacifying the restive Filipino peoples with a combination of brute force and the mobilization of local hirelings, U.S. military authorities replaced Spanish feudalism with a neocolonial administrative model later dubbed “Cacique Democracy.” Named after the Spanish word for indigenous leaders who were co-opted and granted feudal lord status, the cacique model entailed the U.S.’ outsourcing of local rule to pliant landlord clans, local elites, and corrupt bureaucrat capitalists — who enriched themselves and suppressed popular unrest while expediting the transfer of wealth to the imperial center in the United States.

Seeking to escape poverty, upwards of one hundred thousand Filipino migrants played a crucial role in the industrial development of the United States’ Pacific empire — as virtual slaves on the big agribusiness fields of Hawaii and the West Coast, as cannery workers in Alaska, or as maritime stewards in the U.S. Navy. Many Filipino workers faced mistreatment and virulent anti-Asian racism in the United States, driving them to channel their resistance through multiethnic and leftist associations alongside their Chinese, Japanese and Korean co-workers.

When the U.S. government and agribusiness concerns created the Philippine Commonwealth in 1935 along cacique comprador lines, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) was also created as a subsidiary of the U.S. military to ensure order.

As historian Epifanio San Juan Jr. wrote in his critical volume U.S. Imperialism and Revolution in the Philippines, the country “became a model of a pacified springboard for naval operations and for breaking into the Chinese market. These were, in fact, the original reasons for the Philippine adventure.”

By 1942, the Commonwealth of the Philippines faced a brutal occupation by the Imperial Japanese Army, which faced stiff resistance from the communist guerrillas or “Huks.” Demoralized and facing defeat by the encroaching U.S. and allies, the Japanese exercised horrific brutality against civilians: in Manila alone, around 100,000 men, women, children and infants were brutally murdered, tortured, mutilated and raped. The country was left in ruins following the war — 80 percent of the economy had simply been destroyed. After the victorious U.S. granted the Philippines its independence, the wealthy caciques and elites remained loyal to the U.S., developed a close relationship with post-war Japan, and continued the war to suppress the communist rebel Huks.

Duterte’s “independence”: chronicle of a failure foretold

“The country was the principal rearguard and staging point for the U.S. war against Korea and later against Vietnam,” William I. Robinson — noted author and professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara — told MintPress News:

The United States eventually established a string of some 300 military bases in seven Asia-Pacific countries. Its military presence in the Philippines stood at the center of this web. The U.S. military presence in the Philippines was also the hinge around which counterinsurgency was organized against the New People’s Army in the 1970s and 1980s.”

By 1991, however, Philippine President Corazon C. Aquino and U.S. President George H.W. Bush were forced to cave in to the demands of militant mass movements and nationalist officials that U.S. control of the territory its bases covered be handed over to the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) — bases once crucial to U.S. military interventions in China, Korea, Indonesia, the Middle East and Vietnam.

At the end of 1992, the U.S. handed over the keys and walked away from U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay, its largest overseas military installation — a move seen by U.S. senior officials as “irreversible” in the post-Cold War era but criticized as a sign of U.S. decline in Asia.

These victories for genuine independence proved short-lived: in 1999, the U.S. and the GRP signed the Visiting Forces Agreement, paving the way for the annual U.S.-AFP “Balikatan” exercises and granting U.S. troops virtual immunity for crimes such as rape and murder committed on Philippine soil. Once again the country’s sovereignty was on the line.

“The events of September 11, 2001, and the farcical ‘war on terror’ led to [a major] return of U.S. military personnel,” Robinson said.

Following September 11, 2001, the U.S. re-committed to all-out intervention in the fight against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and the New People’s Army — not because these groups had anything to do with the attacks on the World Trade Center, but because they were fiercely opposed to the U.S.-controlled “puppets” in the Manila government and enjoyed significant support in the guerrilla fronts, villages, and cities of resource-rich Mindanao.

U.S. imperialism also fought for the hearts and minds of Filipinos through its “soft power” mechanisms: loans, nongovernmental organizations, Hollywood films, philanthropy, influence in academia, and USAID assistance.

Meanwhile, the country’s national police and AFP used the considerable arms and training provided by the Pentagon to control unrest through the use of martial law, warrantless arrests, enforced disappearances, rape, extrajudicial murder, and collective punishment tactics like food blockades. This was cacique democracy for the modern era.

In recent months as the Trump-Duterte relationship grew sweeter, the trend has only worsened — as police and soldiers have targeted everyone from progressive clergy to human rights activists and entire communities of indigenous people seen as sympathetic to the communist fighters of the NPA.

In light of Manila’s symbiotic relationship with Washington, Duterte’s claimed effort to wrest the country from the controlling grip of his U.S. overlords has been the chronicle of a failure foretold, to paraphrase Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez. “It is very clear to Trump that the Duterte regime is securely a puppet of U.S. imperialism,” Jose Maria Sison told MintPress News, explaining:

All the major treaties, agreements and arrangements that bind the Philippines to the U.S. economically, politically, culturally and militarily remain intact. Trump’s comment reflects the fact that the U.S. dominates the Philippines as its most prime real estate in Southeast Asia and is an important forward base of the U.S. in the East Asia-Pacific region.”

In Part Three, we will conclude the series with a comparison of Operation Pacific Eagle to the notorious counterinsurgency initiative “Plan Colombia” and look at how the new Pentagon mission enables the U.S. to continue encircling China with its military bases.

Elliott Gabriel is a former staff writer for teleSUR English and a MintPress News contributor based in Quito, Ecuador. He has taken extensive part in advocacy and organizing in the pro-labor, migrant justice and police accountability movements of Southern California and the state’s Central Coast.